A dancer, tango dance teacher, milonguero, choreographer, tango singer, and actor, Pancho Martínez Pey is now a member of the International Dance Council (CID – UNESCO), after a career of almost 40 years in dance, which began with folk dance. With teachers like Héctor Falcón and Susana Rojo, Rodolfo Dinzel, and Petaca – among many other milongueros’ masters – Pancho has never ceased to be among the leading figures of tango since his debut in Gloria & Eduardo Arquimbau’s show. His starring role in «Tanguera, el Musical» stands out, as well as his participation in Nacha Guevara’s musical, » Tita: una vida en tiempo de tango.» He has worked in the most famous tango houses, from the legendary Caño 14 to Rojo Tango. He has also been a judge at the Tango World Championship from its early days. He has appeared in several films, including “Un tango más” (“Our Last Tango”), the documentary about the lives of María Nieves Rego and Juan Carlos Copes. And, for over 20 years, he has been the dance partner of the great María Nieves Rego. In this interview, Pancho not only shares his story but also reflects deeply on the current state of tango practice, both in social and stage contexts.

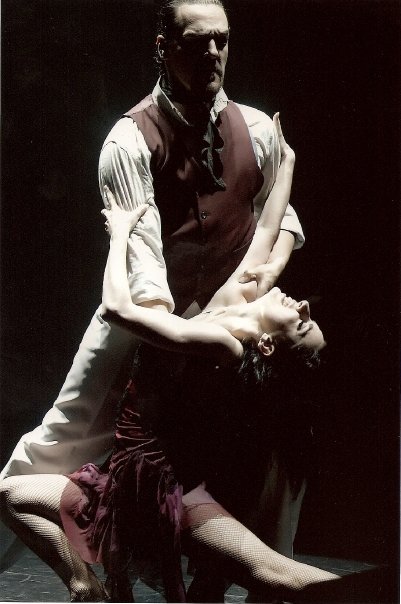

Ph. cover: terrygalindo

Pancho, you come from a family of musicians deeply rooted in Argentine folk music. What did the experiences lived at home awaken in you? Ord did you simply go with the flow?

It was what we lived at home because my dad and my uncle were musicians who had been playing together since they were 18. My dad was an excellent guitarist, an arranger, and a composer; in fact, he composed the music for a couple of renowned folk dances. Besides the guitar, he played very well the double bass and the requinto, which is the small guitar for boleros. Every weekend at home, there was a family gathering, and it was all about playing and dancing. Before I was 8 years old, I was already dancing with my mom at “peñas” (folk music gatherings). On April 2, 1982, my dad made his debut with the folk group, the day the Falkland Islands were recovered, and I remember being a part of it and dancing with my mom.

Was your mom a professional dancer too, or did she dance informally?

No, she wasn’t a professional dancer, although she wanted to be one, but there were many constraints back in those days: “…that she couldn’t”, “…that they wouldn’t let her”… many reasons. My old lady loved dancing Argentine folk music, and when Young, she had also done Spanish dances. One day she met my dad, and here I am.

Do you play any instruments as well?

I started as a percussionist. In folk music, I played the “bombo” (a large Argentine drum), and in the ballet, we did “malambo” (A traditional Argentine dance that is often characterized by fast footwork and rhythmic stomping. It’s typically performed by male dancers and is an important part of Argentine folk), “boleadoras” (Traditional Argentine weapons used by indigineous people for hunting, consisting of two or more balls connected by cords or thongs. In malambo, dancers swing the boleadoras in circular or crisscrossing motions to create a rhythmic and visually impressive effect), “bombo”, all percussion.

Which ballet was that?

It was the Argentine Ballet Zupay, directed by Juan Cáceres, «Zupay,» and Elba Maceira, who have been in Tenerife for several years now. I joined the ballet when I was 12 years old. Before that, I used to attend peñas and took some Argentine folk-dance classes. At the same time, I also started with the ballet at the National School of Dance, which was called «Tiempo de Folclore.» But I used to go to every peña, just as now I’m a “milonguero” -because a milonguero is someone who goes to the milonga every night, and goes to every milonga to dance.

You were a “peñero” (a regular at “peñas” paraphrasing “milonguero”).

I was a “peñero”. I used to go with my dad and my uncle. We would carry the equipment, dance all night until the gathering was over, and then head back home. That’s how I spent my weeks. You can’t imagine how it was the first time I bought my own boots! I was “zapateando” (Argentine folk tap dancing) all day.

And in your early performances with the ballet, did you already feel something being in front of the audience, or was it just the pleasure of dancing?

It was the pleasure of dancing. I always loved to dance. In a way, people saw that spark or that something special in me; those who knew me as a child spoke highly of me, but I didn’t feel it. I was a kid, and all I wanted to do was dance.

How did you transition from folk music to tango? How did you get into tango?

We started doing tango choreographies in the ballet. My first tango teachers were Héctor Falcón and Susana Rojo.

Oh, what a game plan! What did you feel the first time you saw them dance?

I loved them; they were fantastic. Their presence, their style. They would embrace each other, dance, and it was like, «Wow!» They left you astonished.

So, that’s where you began your tango journey?

That’s where I started, choreographically. Then in ’92, a guy who had been part of my dad’s folk music group and had found work in the Verbenas circuit in Spain called me. I was working at a bank in credit cards and had just taken some classes with Copes. I said yes and left everything behind. I spent a year and a half traveling all over Spain. We played a bit of everything to make people dance. I played the drums, sang, and during breaks, the keyboardist and I would dance tango and Argentine folk music for the audience while my friend sang with his guitar. And I would end with a malambo.

And… what happened?

It happened that the audience went wild. They loved it! I’ll never forget, a town called Toreno, located up North of Spain, in the way to Galicia. We were in the square – which was huge – along with a wind orchestra, and there must have been about three thousand people. It was crazy! When we played, got down, and danced, the audience went crazy.

And what did you hook from that journey for your personal story?

I went with a lot of enthusiasm, like any young guy: “I’m going abroad, I can make money… When I come back, I’ll open a bar, a karaoke place, with a stage for shows and a dance floor with live musicians…” and so on. And I came back with less money than when I left! (Laughs).

Though, you gained in satisfaction, even if the money didn’t follow.

Exactly. That trip left a mark on me, it made me grow a lot as a person. Maybe, if I had stayed here, I wouldn’t have seen what I saw when I was abroad, about myself, my relationship with my family, and many other things. Also, about what I truly wanted. I’ll never forget it; I was very sad because, at the time, everything was more difficult. They sent me VHS tapes! My friends sent me cassettes and said, “What are you doing there? Why did you leave? Come back.” I was really down. We all were kind of sad. And one day, as we were returning from a performance…

Do you remember why you were feeling down?

It was because of the nostalgia… We missed social codes… friends calling you to meet for coffee in two seconds, laughing about the same things…

What nourishes you.

What nourishes you. Having to explain to a Spaniard how we thought something, so that they can have fun with us. And because I was still quite Young, mentally, that trip helped to mature my mindset.

So, what happened next? You were coming back from the performance and…?

There was a radio program hosted by Alberto Cortés that we used to listen quite often, and on that day, he closed by talking about these things: nostalgia, and so on. And he ended with a tango. The three of us were in the truck’s cabin, traveling, and you know when you feel a void, like there’s no air, nothing, and you only hear that song? I felt it as if the glass was breaking, as if everything was starting to crack.

The movie was starting to crack, the movie screen.

Exactly. It was a very strong nostalgic moment. I feel that it was there when the tango came, touched me, and made a “ping.”

Let’s say “tango waited for you” until then (referring to a celebrated quote of Anibal Troilo: “Tango awaits you”), that’s when it reached you.

Exactly because it’s tango that looks for you; you don’t look for tango. You can listen tango music all day long, as much as you want, and not understand a thing. But when you’re ready, tango comes, touches you, and says, “Boom! You’re mine,” and it enters.

Do you remember which tango it was that it entered with?

I think it was “Volver.” I don’t want to lie; I know it was Gardel, but I can’t specifically recall whether it was “Volver” or “El día que me quieras.” But from that moment on, the only thing on my mind, was to return. And I came back home.

«…it’s tango that looks for you; you don’t look for tango. You can listen tango music all day long, as much as you want, and not understand a thing. But when you’re ready, tango comes, touches you, and says, “Boom! You’re mine,” and it enters.»

Do you remember which tango it was that it entered with?

I think it was “Volver.” I don’t want to lie; I know it was Gardel, but I can’t specifically recall whether it was “Volver” or “El día que me quieras.” But from that moment on, the only thing on my mind, was to return. And I came back home.

Did you return with the idea that you wanted to continue with something related to what you had experienced?

I came back with the clear idea of becoming a tango artist, so I arrived with a specific goal. Additionally, when I returned, most of my fellow dancers were way ahead, and I had only retained the choreographic knowledge I had, so I was desperate. People recommended me that I take classes with different people, so I started taking classes with Celia Blanco and with Dinzel. And also, since I had taken classes with Pepito Avellaneda before leaving, and thanks to that, I started to get to know many milongueros like Rodolfo Cieri and others; when I returned, I was specifically looking for all of that. I got hooked on Dinzel and spent a year and a half in his studio while also going out to dance.

Where did you go to dance?

The first place I went to dance was the “Cochabamba” practice, where Mingo (Pugliese) gave lessons, and Gustavo Naveira organised the practice and also taught there. During that time, everyone used to go there to dance: Fabián Salas, Pablo Verón as well. I also started going to dance at milongas: Akarense, Almagro… When I went to Almagro, it was… a flash. It was a flash.»

Why was it a flash?

Because I thought I could dance, but I learned the true of tango at the dance floor of Almagro. It was the first time I entered a place and saw that human tide moving all together at once, in unison.

That famous human tide that is no longer seen, being very chaotic now the dance floor.

Now, there are all whirlpools. And the Almagro dance floor wasn’t large; it was like the Canning dance floor, for instance, but it had a tremendous circulation.

And how did that change your perception of your own dancing? Why do you say, “I thought I could dance until I entered Almagro”?

Because I realized that I didn’t know how to walk.

Are you referring to moving fluidly in the round along with the crowd or to stepping correctly?

Walking, just walking because when I attended Dinzel’s classes, they were held in a room, and we did everything in place. Everything was very intricate and technically excellent, and you learned a lot about body control. But it had nothing to do with making a displaced figure or walking four meters. So I started going to Almagro to observe. I would sit at a table and watch. I was embarrassed to go out and dance because every time I did, I bumped into everyone.

«Tango leaves you naked. You see people dance, and you see who they are: You see the one who communicates, the one who is cold, the one who is distant, the one who doesn’t allow themselves to be affected, the one who seems dying while dancing a tango. It leaves you naked.»

Plus, who knows if they would accept your invitation to dance!

Exactly. Although I was fortunate in that sense from the beginning, since I had an acceptable and generous dance. People always acknowledged me that dancing with me was enjoyable.

“Generous,” do you know why?

In a way I think it’s a matter of adaptability, I adapt well to the other person’s body. And, at the same time, even though I hadn’t yet defined my style or anything, I think it had to do with the fact that I had a dance technically developed. And it always helped me that I never had a fixed partner.

You had to particularly develop the talent of being able to adapt.

Because there were few tango venues and few dancers, and most of them came from folk dance, so most were choreographic dancers. There weren’t really dancers that you could say, “I see you dancing at the milonga.” Few truly knew both. I was fortunate to start with the milonga and the stage simultaneously.

Where do you think that ability to adapt comes from, even back then, despite the fact that, of course, you’ve kept on working on it?

I believe it’s mainly due to the love and eagerness I had for doing things, right? It’s also a natural trait I have, which is why people calls me Pancho. I’m called Pancho precisely for being Pancho (In Spanish, the adjective «pancho» is often used to describe someone who is relaxed and easygoing). I had struggled to be called by my name… but Pancho always won.

So, is it nice to dance with you because you make your partner feel calm, supported… as if you transmit your natural tranquillity to her?

I’m not sure why… Maybe because I enjoy having a good time, always. I do what I love, what I enjoy, and by doing so, I am happy, and that happiness, that positive energy, radiates.

Where did you start? Both on stage and in the milongas.

In ’97, I was dancing in Michelangelo with Gloria and Eduardo, and I was teaching in Almagro with Dolores De Amo. We had seventy students every Sunday; it was a complete madness. I went there, and boom! Everything exploded, since then, I never stopped.

How did you learn to walk by sitting in the milonga and watching?

Watching also teaches you if you know how to watch. I watched how people walked, how they moved and circulated together. Besides, I started to meet all the milongueros – Pedro Monteleone, El Alemancito, Portalea, Poroto, El Gordo David, El Tano Nicola, Carlitos Moyano, a lot of people… Petaca!, who was my great teacher – and they would chew you out.

You would be dancing in the milonga and they would come and say…

They would chew you out. They’d come and say, «What are you doing? Don’t do that.» The milongueros were watching you all the time, they didn’t miss a thing. Petaca came every Sunday to see how I was teaching the class and used to say, «You have to tell people the truth, don’t lie to them with a step you don’t know how to do. Show people how you dance and teach them what you dance. Don’t listen to ‘la gilada’(fools, numbskulls, from the Argentine slang “lunfardo”, refering a group of people who behave senselessly), he said. And that’s how I got started; these things also shape you, you see?

Shouldn’t your generation take over the role of caring for the milonga? Because now many of those milongueros are gone. Besides, it’s another era; perhaps people wouldn’t listen to them now. But they might listen to you as maestros.

Look, in my opinion, it happened a black hole in tango due to the 2001 crisis (Argentine crisis of 2001, which involved a hyperinflationary spiral and the abandonment of the peso’s peg to the US dollar, known as the convertibility plan, resulting in a sharp devaluation of the Argentine peso, a freeze of bank deposits, and a significant increase in poverty and unemployment.). In 2001, the maestro who danced left, the assistant to the maestro left, the best dancer in the class left, and the one who didn’t dance well but was a bit clever left. Almost no one stayed here. Most of the milongueros who could leave also left. Only beginners stayed and a few teachers. And most people didn’t leave for the love of tango and to expand our culture… they went away to make money. So, as they went to make money “gancho” (leg hook) courses, “barridas” courses (sweeping), “sacadas” courses, and courses of this or that began to appear, but nobody taught how to circulate or walk, or tango with a social sense. There were few who did. I would almost say that the only one who was breaking apart with that – I remember it because I know him – was Pedro Monteleone, who went to Italy and tried to carry that line, to some extent. Apart from him, most of those who went abroad went to make money.

«…if we all did things to get better and not just trying to scrape by, everyone would be much better off. …We all need to make money, but we can make money teaching well.»

But everyone, in one way or another, comes back at some point. And some are here, like you.

Yes, today there are many people doing that. But we are also very careful about how we say it. Milongueros didn’t have much tact. «See the step, kid?» «Yes, but can you teach it to me?» He would show it to you and say, «There it is, did you see it? Do it.» And you had to figure it out as best as you could. Nowadays, you have YouTube, a teacher explaining how you should move your metacarpal muscle to reach the psoas for the axis and get to the brain to have positive thoughts about your dance partner, you know? Eighty million crap things have been added to the tango merchandising. Tango has turned into merchandising, and with the appearance of the World Championship, the interest in selling tango increased even more, leading to this thing that there must be an exhibition, an orchestra, or something in every milonga to attract people. Back in those days, people went to dance. When restrictions were lifted after the pandemic, it was amazing. Since there were no tourists, those who danced went to the milonga to dance! That was great; it reminded me of the time when I was going to Almagro. People went there to dance just for the sake of dancing; there was no one to sell anything to.

«…“gancho” (leg hook) courses, “barridas” courses (sweeping), “sacadas” courses, and courses of this or that began to appear, but nobody taught how to circulate or walk, or tango with a social sense… a teacher explaining how you should move your metacarpal muscle to reach the psoas for the axis and get to the brain to have positive thoughts about your dance partner, you know? Eighty million crap things have been added to the tango merchandising. Tango has turned into merchandising…»

It didn’t last long.

It didn’t last long; the 2021 World Championship took place, and everyone came, and the nonsense started all over again, and everyone travelling abroad to make money. Fine! We all need to make money, but we can make money teaching well.

And back in those days, if I’m not mistaken, if there was any hierarchy, it was based on dancing well or not. If you didn’t dance well, nobody would dance with you, which forced you to improve your dance to be able to dance with someone. Unlike now that they dance with you -you being a maestro with a lot of tango-, and next they dance with someone who doesn’t know how to step or embrace, as if it doesn’t matter.

Clearly, but they wanted to break with that, and began to appear relaxed milongas where the “cabeceo” (nodding head) no longer existed. Either you’re sitting and talking with someone, and anyone comes to take you out to dance.

Oh, yes, and they interrupt your conversation without even flinching.

Not only do they interrupt, but the person who is being interrupted goes to dance. In other words, he or she supports the persons who came to interrupt… This is happening a lot abroad where people go to dance, and to dance, and to dance aimlessly, as if they were going to the gym. And the times I’ve been abroad, and I’m invited to dance, if you say, «No, I don’t feel like dancing,» they gave you the look because they think “This guy believe he is …

…Pancho Martínez Pey!

…a star?” (laughter) No, I’m not a star, but you don’t understand what it means to go dancing. You dance when you feel like it, but you can also sit down and enjoy the night talking with your friends or listening to tango because you like it, and you’re not obliged to dance. The point is that they don’t understand the concept of choice; they confuse the lack of choice with rejection. People can’t stand not being chosen, they can’t stand it. And, on the contrary, they have to understand that cabeceo is there so you don’t feel bad. But they take it as… «Oh, he’s so cocky,» or whatever.

«The point is that they don’t understand the concept of choice; they confuse the lack of choice with rejection. People can’t stand not being chosen, they can’t stand it. And, on the contrary, they have to understand that cabeceo is there so you don’t feel bad. But they take it as… «Oh, he’s so cocky,» or whatever.»

It gets confused being democratic, with you having to hug everyone. But democracy is based on the right to choose, which implies respecting everyone’s right to say no without needing to give reasons why.

Exactly. If not, it has been imposing it on you, which is violent. When I went to Almagro, there was a girl who I always liked watching dance, and I wanted to dance with her, but she didn’t look at me, and she didn’t look at me, and she didn’t look at me until I couldn’t take it anymore. I got up, went to her table, and said, «Do you want to dance?» She gave me the look and said, «Well, now that you’ve come over here, I guess I’ll have to go.» She got up quite upset, and we went to dance. Then she softened up; she liked how I danced, we started talking, and over time, we became friends. But I’ll never forget that first time. I never went to a table to ask a girl to dance again, never.

The same thing happened to me when I had the habit of pulling with my arm before moving, and Natalia Games cured me of that. We were in a class at Canning, and I said, “Can I lead you?” She replied, “Sure,” and as soon as I grabbed her and did this, she yelled, «What are you doing?!» I got scared as if I were hurting her, but I never pulled anyone again, you see?

And, on the other hand, once I was at La Viruta on one of those nights when I didn’t feel like dancing and avoided all the glances. There was a dancer – with whom I’ve danced professionally, and we’re great friends – who kept looking at me and looking at me until she couldn’t take it anymore. She turned and said to me, “When are you going to invite me to dance?” I replied, “I’m sorry, but not today. Some other time, when our eyes meet, and we both agree, we’ll go dance.” I think it was the next weekend or the next time I went to La Viruta, but these situations, which are funny deep down, are necessary. Those codes added quality to tango. Nowadays, all of that is not valued, and quality is lost.

The truth is that we women have always had the chance to ask someone to dance using cabeceo, without needing to go to the table like they do now

Always. Women have the power. They’ve always had it; all the milongueras will tell you that. They wouldn’t accept a guy if they hadn’t seen him dance first, and he had to dance well. Nowadays, women go out to dance just to avoid “planchar” (It refers sitting out for an extended period without dancing neither engaging socially in the milonga).

Just to move.

Just to go to the gym. And going out to dance with someone you wouldn’t choose just because you didn’t want to miss dancing that tango is very selfish. The primary thing about this whole thing is the encounter with another person to enjoy tango or the “tanda” you want to dance. If you’re okay with dancing with anyone that means that your frankly don’t give a damn who you dance with, you don’t care neither how he or she moves, nor how they feel. For that, you could dance with a pillar, and would just work. I insist, that’s very selfish.

«This is happening a lot abroad where people go to dance, and to dance, and to dance aimlessly, as if they were going to the gym.»

Returning to your professional trajectory, how was that experience with Arquimbau?

Fantastic. Think about it, I went from the folk ballet to dancing with Gloria and Eduardo! I mean, I entered at the top, and they fully accepted me. They were wonderful, really. And Eduardo, a genius, a maestro, not just in dance, but in life, in the milonguera life, in what tango is. Tango is you.

What does «Tango is you» mean?

Tango is you and how you relate to people, how you experience it, how you express yourself. Tango leaves you naked. You see people dance, and you see who they are: You see the one who communicates, the one who is cold, the one who is distant, the one who doesn’t allow themselves to be affected, the one who dies while dancing a tango. It leaves you naked.

How did Arquimbau manage to get you to bring that to the stage?

Because Eduardo is history. It’s the same as with María or Copes. You learned history when they talk about how they used to go to dance in the “corralones” (corrals) of Mataderos, or all those things we never experienced, just saw in photos but don’t understand. And when they tell you all those stories, you began to understand, in a way, the beginning of things and what was happening. So, you watch «Sucesos Argentinos» (The first Argentine cinematic newsreel, at a time when television did not yet exist in the country, shown at the beginning of cinema sessions) and you flash back to what they told you about when they were young and went to the neighbourhood club, and the orchestras played, and there were five hundred people dancing on the dance floor, and was absolutely crazy. All of that teaches you too.

What were the milestones or thresholds in your career, like when you arrived in Almagro and said, «I don’t know how to walk, I don’t know how to circulate»?

The first one was when I auditioned to join the Parque de la Costa ballet, around the same time I started at Michelangelo. I made it through the initial selections, but in the final round, I didn’t get in. However, by one of those twists of fate – and nothing happens by chance – Jesús Velázquez, who had been selected, got an offer for a tour in China and called me to replace him. Patricio Touceda, who had been selected with his partner, had recommended me. At that time, I was working on the trains. I started at five in the morning and finished at one in the afternoon…

Was that an administrative job?

I was a ticket seller at the Floresta train station, and within a year, I was promoted to station chief in Moreno in the morning. I went on from selling about fifty tickets on a good day to selling twelve hundred and becoming the station chief. I was in charge of a cashbox with three thousand dollars and three employees under my responsibility, plus the ones working on the little trains that went to Luján and Mercedes. It was crazy. After work, I’d go home, change, eat, and around three in the afternoon, I’d head to Dinzel’s place until ten at night. I would lock up the studio.

Seven hours of rehearsal every day! Not bad! A full workday! Actually, you worked double shift – one on the trains and another in dancing.

That’s how I spent two years of my life until I got the opportunity at Parque de la Costa.

Did you find out why you didn’t get selected in that initial audition, despite them later calling you back? Did you figure out what you needed to improve?

It was related to technical aspects of ballet. I went from dancing folklore to tango and had no idea how to do a barre exercise. I’d spin, and by the second turn, I was already starting to stumble, and the first turn was just a fluke. With time and lessons, I improved.

«There is a huge difference between dancing tango and being a dancer… Many people are very talented dancers, but they can’t be artists because they are not made for the stage. Conversely, some people are excellent artists and dance tango very well on stage, but they can’t dance in the milonga or they do it but with no reaction from the public. They are two opposite things, and it’s challenging to do both; you have to understand what is required in each place.»

What was the next threshold or challenge that made you grow artistically?

When we debuted in Tanguera, Junior, who played the lead role, cut his finger badly during the knife fight scene, and I had to step in to cover for him. That’s how I started as a cover; three months later, Junior left, and I became the lead. That was another threshold because I jumped up about twenty levels in one go. Tanguera made me evolve a lot as a dancer. Or, better put, it helped me develop my talents.

What did that threshold demand from you?

Everything, because there is a huge difference between dancing tango and being a dancer. I became a dancer there. And Tanguera demanded a lot from me because I had the lead role and had to act, even though I didn’t have any lines, but I had to act.

Did you discover your inclination for acting there, or did you already know that you wanted to act?

I had always been a clown. At home, when we had people over on weekends or during family gatherings, I would always dress up or do a sketch, imitating my dad coming back from work. In school plays, I was always cast to act. I had secured the role of San Martín.

By the time Tanguera came around, had you already done the movie with Carlos Copello?

Yes, the first thing I did scenically was the movie I filmed with Copello, “Tango Fatal,” and that was before Tanguera. In fact, I started doing some things with a friend named Marina Vázquez. She was the one who told me, “You’re an actor.”

Why did she say that? Was it because of how you performed?

Because of how I performed, how I understood the directions, and how I could express myself. “Well, teach me,” I said, and we started to try out some things. But I never took any intensive acting course; we never have time, you know how our job is. The schedule is a mess, not only changing from day to day but within the same day! Afterward, I did some more studio work with Gaia Rosviar, who is also a friend, and a dancer and a singer, who was in Cabaret, and with her I did take some courses

I read that you also enjoy writing or that you studied narrative. Is it correct?

I’ve always been interested in it because I’ve always wanted to put together a script or something like that. I started writing some things, but they remained unfinished. What I have are more like scattered ideas that I managed to write down. To develop them, I’d have to talk to someone who really knows how to do it.

Because I also get tired of seeing people who… well it’s fine. Actually, I think it’s great, that everyone does things because everything contributes. The truth is that there’s more criticism than action, and we need people who do. When I worked on the production of the World Tango Championship, back in 2017, I was asked to find tango shows, and there were none! By that time, shows like Tango Pasión, Tango X2, and Forever Tango had already disappeared.

«What do you think is the reason for the decline of these types of shows or shows tours? In a way, it was because of the global economic crisis, which led to a drop in investment by production companies. Also, tango shows didn’t evolve.»

In what sense it was due to the non-evolution of tango shows?

Because there is no musical comedy: a spoken, sung, and danced story. In fact, the success of Tanguera was due to the fact that, even though it was a simple story – the bad guy, the good guy, and the girl in the middle – with the magic that Omar Pacheco brought to it, it had you captivated the whole time, like, «What the hell is happening?» More than the script, it was about how the story was told and unfolded, thanks to a good direction. We performed it in places that were not at all prepared to set up the stage, and people applauded standing.

When we did «Tita: Una vida en tiempo de tango» with Nacha (Guevara), Julio (Balmaceda), and Corina de la Rosa, that was a musical. However, in a theatre with nearly a thousand seats, we only worked at fifty percent. There wasn’t much interest in tango.

«Tita: una vida en tiempo de tango».

Dolores de Amo shared a similar view: in her interview she made the point of the need to move from the traditional tango show to one more scripted, where artists not only danced but also had to act, speak, and sing. However, she also pointed out that tango dancers lack the kind of comprehensive training that type of show requires. What’s your opinion on this?

I agree. In general, firstly tango dancers are usually self-taught, and secondly, we are never coached. Once a tango dancer learns how to dance, they start creating their choreographies and forging their own path, and they rarely take lessons anymore. Why? Mainly because work usually comes before personal growth. This is primarily due to the scarcity of job opportunities and the low pay. If someone with a steady income is barely making it, imagine a tango dancer! They either have to dance in Caminito, or spend all their nights as taxi dancers, or do something else. This it what makes your prioritize work over artistic development.

Do you miss those types of shows?

Yes, of course, because I’m a stage guy. I never stopped being an artist, even though I became a milonguero and always have been a milonguero.

But the exhibition you can do in a milonga is not the same; it doesn’t fulfill you in the same way.

No, it’s not the same; in a way, going to dance at an exhibition is simpler. Getting on stage is a whole different thing due to the preparation, rehearsals, lights, atmosphere, audience, seats… And beyond all that because it puts you in a different place as an artist: getting on a stage… it’s getting on a stage!

Many people are very talented dancers, but they can’t be artists because they are not made for the stage. Conversely, some people are excellent artists and dance tango very well on stage, but they can’t dance in the milonga or they do it but with no reaction from the public. They are two opposite things, and it’s challenging to do both; you have to understand what is required in each place. Once, Pablo Verón said, «I love all those who do fusion, but to fuse, you first have to know: you have to know what jazz is, what tango is, what folklore is.»

Sergio Cortazzo made a similar comment in his interview when he said, «Piazzolla, before revolutionizing tango, played with Troilo.»

«He played with Troilo,» exactly.

And Pepe Colángelo shared the same idea: «To revolutionize something, you first need to know the foundations well.»

You have to know what you’re doing and why. Every step has a reason. And most people, even professionals, can’t explain it.

What are you trying to express with that step or sequence?

«Why are you doing it? Explain it, justify it. Most people have no idea, or they can’t explain it. Today, being so easy to scrape by with tango, all of this is overlooked, and everything loses its meaning.

«In general, firstly tango dancers are usually self-taught, and secondly, we are never coached. Once a tango dancer learns how to dance, they start creating their choreographies and forging their own path, and they rarely take lessons anymore. Why? Mainly because work usually comes before personal growth. This is primarily due to the scarcity of job opportunities and the low pay. If someone with a steady income is barely making it, imagine a tango dancer! They either have to dance in Caminito, or spend all their nights as taxi dancers, or do something else. This it what makes your prioritize work over artistic development.»

It’s true! Tango is veryyy generous…

Absolutely. And everything gets distorted. Festivals don’t bring in judges to give classes; they bring in the champions, who may have only been dancing for a year, and so kids teach what they can. Imagine what it’s like for them: they become champions, and suddenly they are in demand from everywhere. I would also be over the moon. The problem isn’t with them but with the criteria of the organizers. What do you create, why, and for what purpose?

You see, in the performance society, as Byung-Chul Han calls our era, everything is measured by results or likes.

Aesthetic appeal sells more than a well-executed step. The dress you wear sells more than how you move your legs.

«I believe that if people would bet more on what they love to do, we would all be happier. In my personal case, even though I have a long professional path, I haven’t always been financially successful. However, I’ve always had wonderful moments that were worth more than anything.»

Tell me about a special moment in your career, one of those measured in heartbeats and not in likes.

I had a teacher for three years, from grades one to three – she was the beloved teacher of all of us, the one who put me on stage for all the school events. After finishing high school, I ran into her, and she asked, «How are you, Bombón?» – she always called me Bombón (sweetie) – «What are you going to do?» I replied, «Well, I’m considering taking a computer course, or maybe studying economics because I’d like to pursue business administration or something like that, you know.» And she said, «Oh, I thought you were going to be an actor.» Boom, that really shook me. A long time passed, and I didn’t see her again. One day, at Esquina Homero Manzi, Gavito couldn’t make it, so we had to dance more to cover all the songs. After the show, the waiters from Homero Manzi came down and called me, «Pancho.» I asked, «What?» They said, «Take this, we got a letter, it’s for you from someone up above.»

Oh, I’m dying!

I opened the letter, and it said, «Hi, Bombón (Hi sweetie). I came to see Gavito, but I found you dancing on stage like the best of the best. I’ll be waiting for you upstairs, Your Miss Elisa.» I couldn’t believe it. I changed quickly, rushed upstairs, and sat down. I looked at her, but I couldn’t speak or say anything. I just could smiled, and she cracked up. I couldn’t believe that she had come to see the show. From then on, we stayed in touch, I invited her to see Tanguera, and whenever she heard I was giving classes or performing, if she could, she came.

in front of the » Usina del Arte», in 2015.

How was the experience of working with María Nieves?

With María, we had chemistry! Right from the beginning. We totally hit it off. The first time we danced at a milonga was in Madrid in 2003, during a tour with Tanguera, at a milonga hosted by Julio Luque and Leo Calvelli. And from that day on, it was like a marriage. She’d say, «Shall we dance another?» and «Do you want another one? Come on!,» and, «Wait!, let’s listen to the next song, and depending on what it is, we’ll keep dancing.» That’s how we spent the night, to the point that we were invited to do a performance the following weekend. And we did it.

What does it feel like as a dancer and tango enthusiast to move and excite the great María Nieves like that through dancing?

Wow… tremendous… thrilling… she is Tango incarnate… and she makes you feel it. It’s very emotional. And full of adrenaline too! And that chemistry that we have is so enjoyable. Despite the age difference, we’re like two kids playing, and we have a great time.

What is María like on stage? How would you describe her?

María is…

That gaze that seems to pierce right through you.

Tremendous. The first time I danced with her, my legs shook. The moment she turned around, planted herself, and looked at me… and my socks were knocked off.

And you already had a few years of professional experience; you weren’t a beginner.

No, I had five years as a professional, working hard. But María is María. She steps onto the stage and can bring down the house. She’s incredible.

Can that be taught, or is it something innate?

It’s innate and it gets enhanced.

With life?

With life, experiences, and hard work. Because, in reality, talent is innate, you either have it or you don’t. If you have it… and if it moves you. For instance, the story María used to tell about she, as a child, dancing with a broom, there it shows whether someone is moved or not. Some people might be gifted but deny it because they don’t accept that their talent is in that area or they might not even realize they have the gift.

«It was the pleasure of dancing. I always loved to dance. In a way, people saw that spark or that something special in me; those who knew me as a child spoke highly of me, but I didn’t feel it. I was a kid, and all I wanted to do was dance.»

And what other significant moments that left a mark on you, like the one you told me about your teacher, can you share?

This has to do with my mom and dad. Despite my mom wishing to dance and my dad to be an artist, he never fully dedicated himself to it. The one time he quit his job to pursue his art, he found out at the airport that the work had been canceled. So he said, «I’ll never leave a job for art, nor for music, again.» So, for me, It was an internal struggle to achieve it. I had many therapy sessions to discuss the subject of outperforming my dad. And it was a very strong moment for me to show my parents that I succeeded.

You had to give yourself permission to reach where he couldn’t.

Exactly. But well, my dad was a such a nice guy, always with a great attitude, always supported me in everything. As he used to say, when I was a kid, I was Cacho’s son, and then he became Pancho’s dad.

If you look back to the kid who used to dance with his mom at the “peñas”, who listened to his dad and uncle playing, did you imagine any of this, or did you discover it along the way?

Look, I have another anecdote. When I finished high school, I started selling courses for flying ultralight aircraft. I never made any money, in fact, I lost a lot of it. But there was a guy in the company who handled human resources, sort of the manager. He was a genius, knew psychology and other things. One day he had us record on a cassette what our dreams were. I did everything he said: I locked myself in my bathroom, closed my eyes, and dreamed that I was traveling, meeting important people, getting on stage, and my parents were sitting in the front row. That’s what I dreamed.

And it happened.

And it happened.

And how did “Pancho, the tango singer”, start?

The main person responsible for me singing is Roxana Fontán.

Oh, well! Someone who doesn’t sing…

No, she doesn’t sing at all. We were working with Gloria and Eduardo in ’97 or ’99, and Roxana would always hear me singing in the dressing rooms until she says, «When are you going to start taking singing lessons?» So I tell her, «When you teach me,» «Well, come over to my house tomorrow,» and that’s how I started. Just as I had a friend who told me, «You’re an actor,» Roxana told me, «You’re a singer,» and I took lessons with Roxana. Then, when I was in Tanguera, I became friends with Lidia Borda and took lessons with her. And then I took lessons with other people, little by little, gradually, but not in a disciplined manner. The pandemic helped me to reinforce that and discipline myself again.

And over time, one also learns that one thing is what you want to do and another is what reaches people, it has nothing to do with it. There was a day, back in my begginings, that was one of my worst day as a singer.. Back then, I sang nicely, but I didn’t have a refined technique. But that was one of those days where you finish the show and say, «Don’t pay me today because it was a disaster.» But, in the end, we went out to greet the audience, and a guy came crying, moved by how I had sung. That day, I learned that many times one has a very high critic, and that my critic has to make room for external criticism, and I have to value what people say from the outside because your own critic will never be satisfied.

«…things falls into place because people see and choose. When they choose you, it’s because you’re doing things right. I believe that everything that came my way was because I was doing things right.»

Is there anything else you’d like to say, whether about art, the stage, or tango?

I believe that if people would bet more on what they love to do, we would all be happier. In my personal case, even though I have a long professional path, I haven’t always been financially successful. However, I’ve always had wonderful moments that were worth more than anything. For example, in the worst time of my life, when I was going through a divorce, leaving my house and my children, I had the opportunity to dance with María at Luna Park. It was one of the first significant tributes to María, and she was really emotional. I was watching the video, and I started to get emotional too. I thought, «If I give up now, everything goes to hell.» So I went on stage, we danced, and we had an amazing performance, with eight thousand people applauding us. Afterward, I was driving back to my home…

The one you were leaving from…

The one I was leaving from, and I couldn’t stop crying, I just couldn’t stop crying.

where they did the interview.

Does that give meaning to everything? Moments like that.

That gives meaning to everything.

Because that’s what holds you to life, right? Even in the worst moments.

It’s what holds you to what you are or what you’ve decided to be or take a chance on. Those are your triumphs. You unconsciously seek them, not because you say, «I want to achieve this,» but because you want all the time to be better at what you do. And things falls into place because people see and choose. When they choose you, it’s because you’re doing things right. I believe that everything that came my way was because I was doing things right.

That’s why you say that if people would bet…

Absolutely, if we all did things to get better and not just trying to scrape by, everyone would be much better off.

Very well, Pancho, we’ll leave it there, «up in the air,» to see if the message lands, even if it happens. Thank you for your time and this wonderful conversation. A pleasure, Pancho.

Pancho Martínez Pey suggests that tango has been plagued with «merchandising,» risking becoming just another market commodity due to the commercialization of its teaching. In addition to this reality, contemporary society, governed by the principles of performance, pushes for hyperactivity and utilitarianism. Things are expected to have a «why.» Time is regarded as capital to be invested in exchange for profit, and if it is not used for a purpose, it is seen as a waste of time. Under the influence of this utilitarian conception, the social gathering which originally was a milonga, increasingly resembles a gym, according to Pancho. It’s no longer sufficient to just listen to a tango or converse with friends to enjoy it. It’s so dissonant as attending a banquet expecting to be served like in an all-you-can-eat buffet. The paradox is that, in this frenzy, life slips away like water through one’s fingers. Without a stop, there is no chance for inhabiting; one must dwell long enough to construct a dwelling for oneself. Furthermore, in the count of “tandas” danced per night, no one is being taken into account, as Pancho rightly points out.

The market has penetrated the very heart of tango, not only in its teaching but also in its practice when attempting to achieve a return on the money invested in lessons or the entrance ticket, valuing the milonga or the event by the number of “tandas” danced or the «level» of the dancers to whom one gains access. In the pursuit of securing a satisfactory moment, the chance of experimenting the extraordinary is lost.

An effect of mercantilism and utilitarianism is that culture suffers and deteriorates, as is it birthed within a community when life extends beyond mere survival. Imagination and creativity flourish in wandering more than in the non-stop running that hinders encounters and finds. It is during the pause when the echoes of what has been felt resonate within the body, leaving an imprint that will procreate experience, adhering to mere memory. After all, “la emoción está compuesta por cosas del ayer”, and it’s in resonance that it would find its beat.

Life takes on another dimension as its episodes gain significance. When the experience is collective, its periodic celebration forms a shared emotional memory that weaves bonds among its participants and a cultural tradition, especially when there is room for recollection in shared conversation. Thus,”la eterna fiesta de los que viven al ritmo de un gotán”, may become a place of reunion and reencounter that enlightens life with joy and cushions its harships with affection, so that life is not reduced to “una herida absurda en la que todo, todo, es tan fugaz.”

Flavia Mercier

Very nice

Me gustaLe gusta a 1 persona